Ginkgo.Your Innovation Partner.

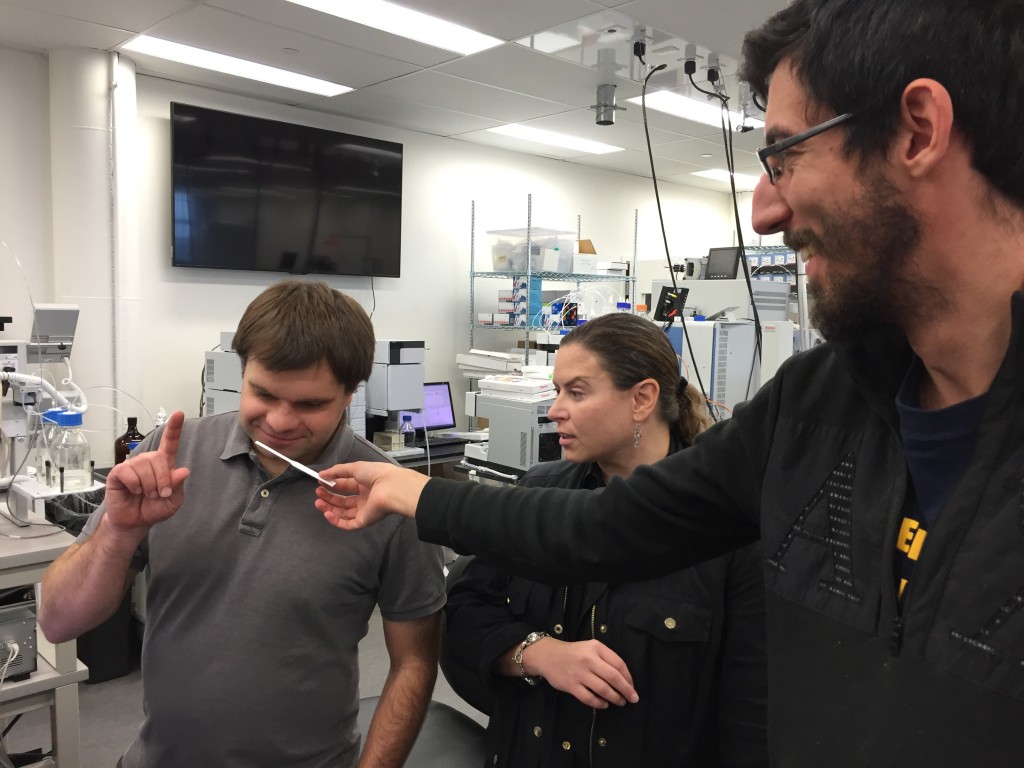

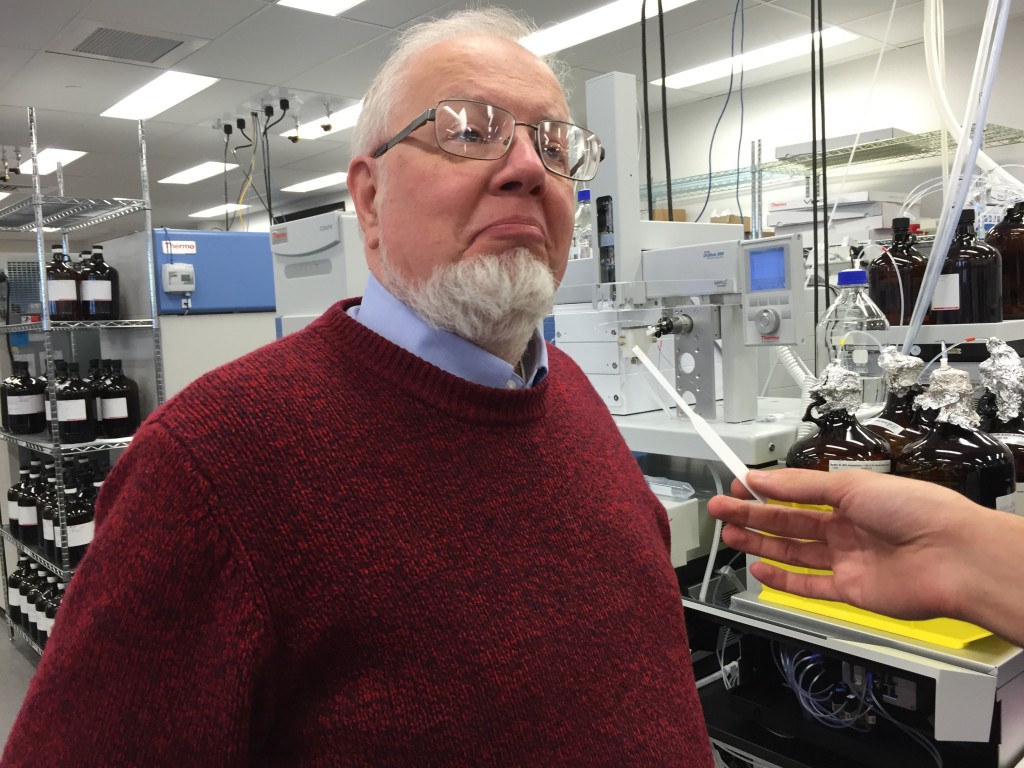

“It’s sort of juicy…fruity?”

“I’m getting melon and…caramel…?”

“It’s just like peachy penguins!”

We’re in Ginkgo’s foundry, Bioworks1, attempting to describe the smell of lactones, a family of scents that have a varied character, adding a creamy richness to everything from jasmine flowers to peach gummy candy to luxury perfume. Their smell is difficult to pin down exactly because they are in so many different fragrances and flavors. Lactones are a crucial part of the scent of stone fruits such as plum and peach, blue cheese, butter, coconut scented sunscreen, and the Gucci perfume Rush. They may be milky, buttery, fruity, creamy, fleshy, peachy, and coconutty, often all at once.

These lactones are part of a new palette of cultured ingredients that Ginkgo is producing in collaboration with our partner Robertet, the French fragrance and flavor house based in Grasse and founded in 1850. We’ve already been working with Robertet on creating a “cultured rose”—a rosy mixture of floral, sweet, and spicy scents produced by engineered yeast. With the cultured rose and these lactones there will be a total of ten Ginkgo cultured ingredients on the palette available to Robertet’s perfumers and flavorists.

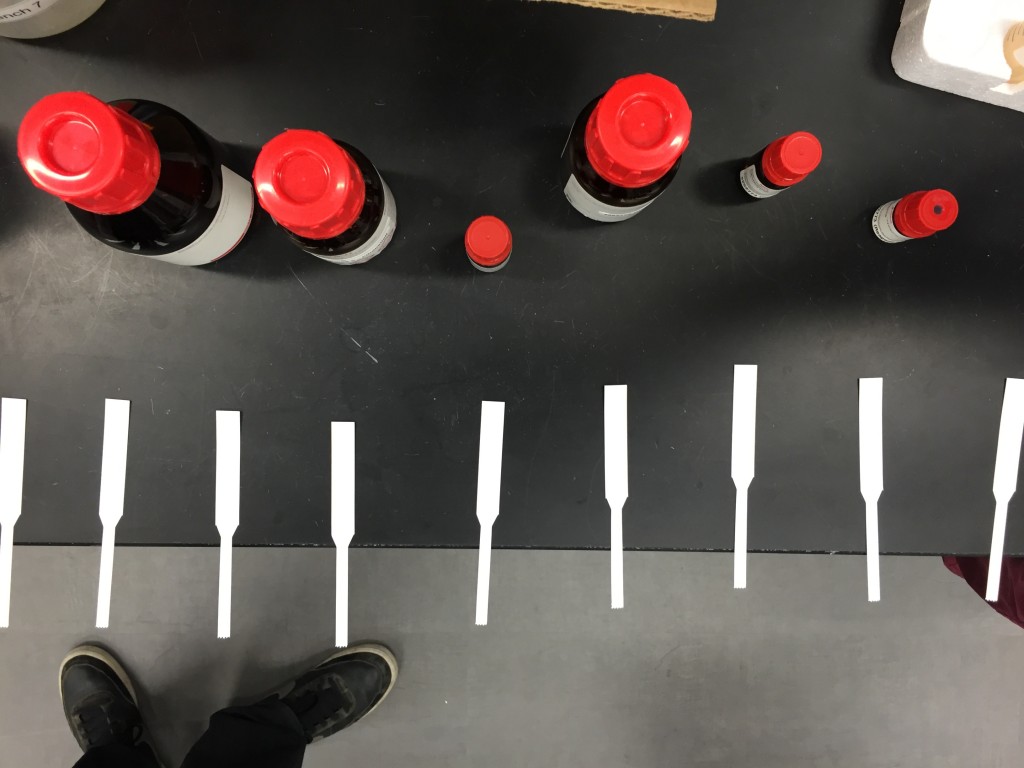

There are many types of lactones, each with a slightly different structure and a slightly different smell. The peachy penguin smell we sampled first was a ten carbon lactone—decalactone (from deca-, Greek for the number ten, and lactone, from the Latin for milk). Add just one carbon atom to the mix and the smell changes. This undecalactone has the same creamy sweetness as its ten-carbon cousin but it smells lighter, brighter, and fruitier. Add one more carbon to get dodecalactone and the smell changes again: sweet and unctuous, with a deeper caramel and coconut tonality.

Lactones are made biologically when cells break down fatty acids—long chains of carbon and hydrogen plus a few oxygen atoms. As the cell chews up the carbons for energy, the oxygen atoms will spontaneously react and bind part of the long carbon chain back on itself, turning the fatty acid into a closed ring that’s characteristic of lactones. Depending on the length of the fatty acid and the position of the oxygen the cell will make different lactones of the deca- undeca- or dodeca- variety.

Many organisms make lactones as a byproduct of metabolizing fats and oils, from single-celled yeasts to tropical trees. While many of the lactones used in perfumes and flavors used to be extracted from tropical plants—like Massoia trees grown in Papua New Guinea—today the majority are made through chemical processes or yeast fermentation because extracting the lactones from the bark kills the tree.

Making lactones via fermentation is a bit like brewing beer, but instead of the yeast eating sugar and producing alcohol, they eat fatty acids and produce lactones. To make cultured lactones we start with a lactone-producing yeast and tailor their metabolism to focus their production on a single lactone. We do this by changing what the type of fatty acid the yeast eat, and by tuning fatty acid metabolism to make the conversion process more efficient. Designers and fermentation engineers work together to match the right brewing process with the right yeast for each target lactone.

Because the biological process of chewing fatty acids and creating a scent is similar for many different lactones, the lessons we learn from creating one ingredient are generalizable to others, allowing us to efficiently expand the available palette. As we learn more from the biology of flavor and fermentation we’ll be able to design many new scent experiences in collaboration with Robertet and perfumers.

Posted by Christina Agapakis